During my just-finished vacation to Poland (described in last post), I had an interesting conversation with a musician/composer guy about a manuscript he’s just finished writing for a novel. His main take was that it had been really fun to write because it provided him with a break from the tasks that he considers his real career, principally composing music and trying to organize stoned, discombobulated jazz musicians. And, because writing is strictly a sideline thing for him, he allowed himself to take his time with it, dropping the manuscript for an entire year and then picking it up again later when the urge struck. Above all, the persistence of fun came across really clearly in the way he talked about his experience with writing.

This reminded me a lot of all things bloggy, naturally– as I’ve written about before, part of the whole point of starting a blog was to find a venue that’s conducive to light, breezy, dilettante-ish writing rather than labored, serious ‘I am trying to be a writer’-type writing. It occurred to me that another, simpler way of putting this is that there’s something inherently amateurish about this format, for better and for worse. This got me thinking about the quality of amateurish-ness, which I would define as when you’re doing something where you don’t exactly know what it is you’re doing and the results perhaps benefit from the circumstance of not knowing.

—–

Many years ago, I went to a show of works by the painter Elmer Bischoff in Oakland. Bischoff made his name doing fantastic figurative oil paintings but then got bogged down and hit a ditch that he described as a ‘state of immobilization.’ The solution came when he dropped oil paint and suddenly began working with acrylics, producing playful, abstract paintings of an entirely different nature. In fairness, I would have to say that his acrylics are never really as good as his oils, but the significant thing is that you can palpably detect the sense of fun re-entering the picture in these later acrylic works. I’ve always remembered his account of this switch in the exhibition catalog that I read at the time: it felt, he said, like “leaving a church and entering a gymnasium. The lights were turned up and there was a very different spirit and feel about the whole thing.”

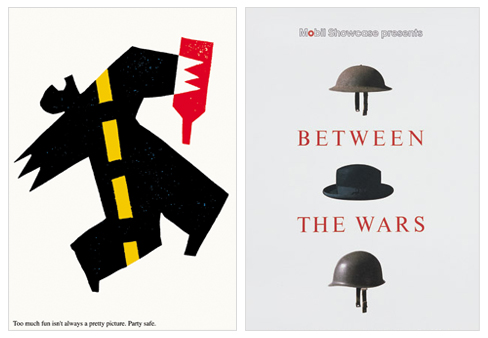

Above: Bischoff oil painting on left, acrylic on right

—–

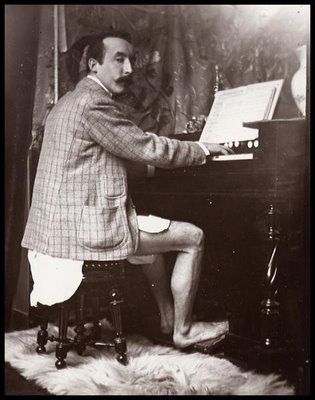

The photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue is an example of an artist whose work exudes amateurism, in part because he created his most famous works when he was a kid between the ages of 6 and 18. Lartigue’s early photos have an evident sense of childishness in all the best meanings of the word. Topically, they show a kid’s world, often taken from a kid’s low vantage point: Lartigue taking a bath, his cousin sliding down a bannister, car races, sports. Aesthetically, they show a world full of energy, motion, speed, fun– the things that kids are drawn to.

Self portrait, age 8

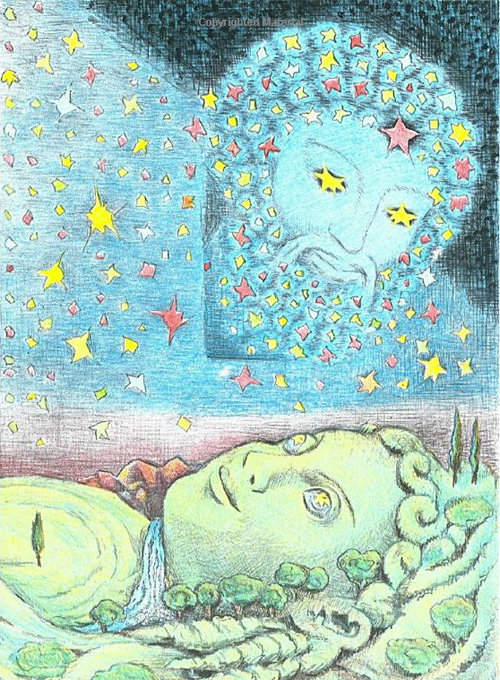

His cousin, Bichonnade

1912 Grande Prix

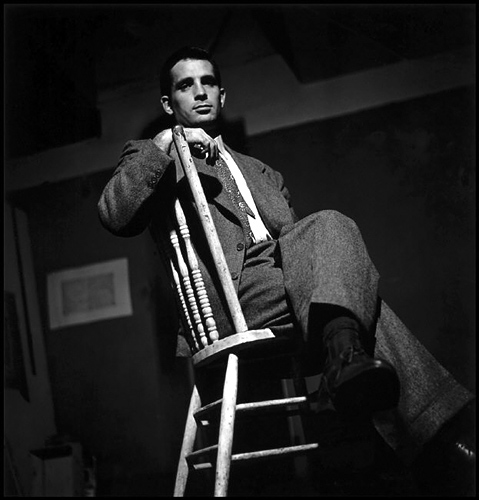

Self portrait, age 15

Bizarrely, although Lartigue took photos his entire life, he supported himself mainly as a painter until his childhood work was rediscovered and rocketed him to international fame late in his life.

The director Wes Anderson is reportedly a big Lartigue fan. There’s a shot of Max Fischer in Rushmore that’s modeled exactly after one of Lartigue’s teenage self-portraits as an homage.