A few nights ago, something inspired me to google the name of a sorely-missed friend of mine who’s been dead for 10 years, a guy named Joe Schactman. Joe was a serious artist and a big influence on my decision to get into graphic design– hell, when we first met, he was about the only person who could tell me anything about graphic design. The nascent internet sure didn’t have much to say, and you couldn’t find anything of note at the public library. I keep a photo on my desk of him sitting in our backyard, focussedly whittling away on a tiny bit sculpture in his hands– Joe was always working on something, so I try to leverage my memory of his industriousness to remind myself to stop procrastinating and get back to work.

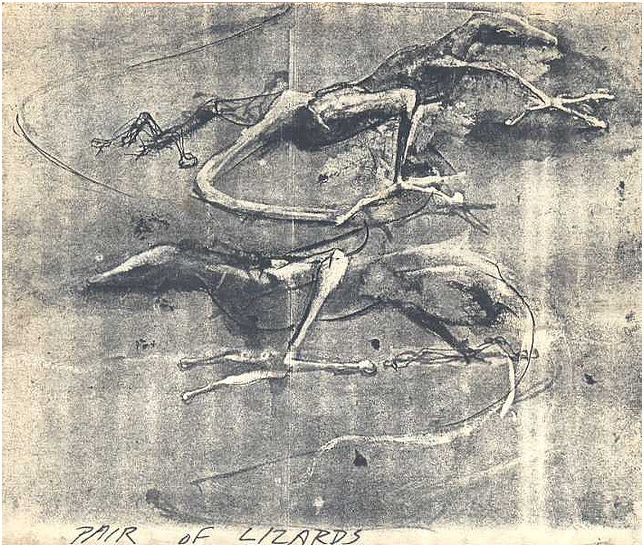

Fortunately, the internet has come along way in the last decade, so my google search of two nights ago led me right away to the Flickr page of another old friend of his who has posted this Schactman drawing ‘PAIR OF LIZARDS’:

One fun thing that Joe would talk about from time to time was the various bizarre live-work spaces that he inhabited as a rag-tag artist in New York City in the late 70s and early 80s. One place, in particular, that he lived in was a giant abandoned factory building somewhere in (if I recall correctly) Williamsburg. Space was rented out for a song to artists, who had all the room they could possibly need there, but the problem was that the place was so vast that you couldn’t realistically heat it in wintertime. So, everyone who lived there would make some kind of teepee-like structure, a tiny sub-unit that they could sleep in and afford to heat. The overall effect, as Joe described to me, was like living in the Serengeti, except you’re also in a giant factory building. In the morning, you would creep out of your tent and start making coffee outside, and then gaze across the vast cement expanse to watch another groggy nomad emerging from his or her tent as well at some great distance. Perhaps friendly salutations would be exchanged or (I like to imagine) some hostile fist-shaking if neighborly relations were momentarily strained. This idea of recreating these kind of primitive tribal patterns within a giant cement enclosure entertains me to no end.