It happened two weeks ago in San Francisco; it’s happening next Sunday here in Prague. It’s the day the clocks move forward, unequivocally my favorite day of the year. If we ever getting around to casting off the shackles of the Gregorian calendar (a task the Czechs have gotten a small-but-significant head start at), I would propose that this become the new first day of the year. Wouldn’t it make more sense to have the calendar roll over on this day, the unofficial start of spring and good times, rather than on some random dark-ass date in the middle of winter? Clocks Go Forward Day always feels like the beginning of something big– how many days can you say that about?

In my opinion, it’s a shame that Clocks Go Forward Day isn’t met with more ritualistic fanfare– a day off from work, a few pagan rites, etc. I feel like we’ve been conditioned to greet it with an air of shrugging indifference, an attitude that I suppose stems in part from the fact that Clocks Go Forward Day is a scheduled routine, a rational measure that doesn’t really feel magical. (Imagine, in contrast, if the change just happened out of the blue one evening with no warning– poof, an extra hour of light! People would be freaking out). But I can’t help but suspect that the constant bean-counting and whining of Daylight Savings Time detractors also impacts our attitude towards this day. You know them: the Oh-no-I’m-losing-one-hour-of-sleep crowd. Let’s just say this isn’t a set of priorities that I have a lot of respect for. In fact, I wish I could do business with it, in a colorful-beads-for-Manhattan-Island-type exchange: ‘Okay, I’ll give you this one shiny hour of sleep in exchange for months of light spring and summer evenings.”

Like everything, the idea of Daylight Savings Time was invented by Benjamin Franklin. During his sojourn in Paris as an American delegate, Franklin observed rows of houses with shutters as the Parisians struggled to sleep through the blasting morning sunshine (incidentally, the same sight that inspired Al Gore to propose the invention of the internet 200 years later). Although Franklin only proposed the idea half-jokingly in a satirical essay, it was picked up by a London builder named William Willett who spent a fortune lobbying for it and managed to get it brought before the British Parliament, only to have it laughed off the floor. I can only imagine what a lonely existence it must have been to be the sole proponent of moving the clocks forward, the endless ridicule one would have been subjected to. Once Germany enacted Daylight Savings Time, Great Britain began to take it more seriously, but only finally started moving their clocks forward after much contentious political debate. The leader of the anti-DST side seems to have been Lord Balfour, the original I-want-my-one-hour-of-sleep bean-counter. At one point, he raised the following imaginative scenario: “Supposing some unfortunate lady was confined with twins and one child was born 10 minutes before 1 o’clock. … the time of birth of the two children would be reversed. … Such an alteration might conceivably affect the property and titles in that House.” Presumably, this was immediately followed by men with powered wigs rioting and tearing up chairs.

The only thing I’ll say in defense of Lord Balfour’s point of view is that the time change does create some really mind-bending and inconvenient scenarios when one is operating between countries that have different DST dates. My attempts to do freelance work for outfits based in the U.S. come to a screeching halt during the two week period between the American and European DST start dates, as we constantly screw up and miss each other’s calls. More surreally, when I went to New Zealand a few years ago, the time change happened at different times and in different directions. For part of my trip, the difference was 21 hours, then 22 for a few days, then finally 23, which made the massive time change feel even more science fiction-y that it already would have.

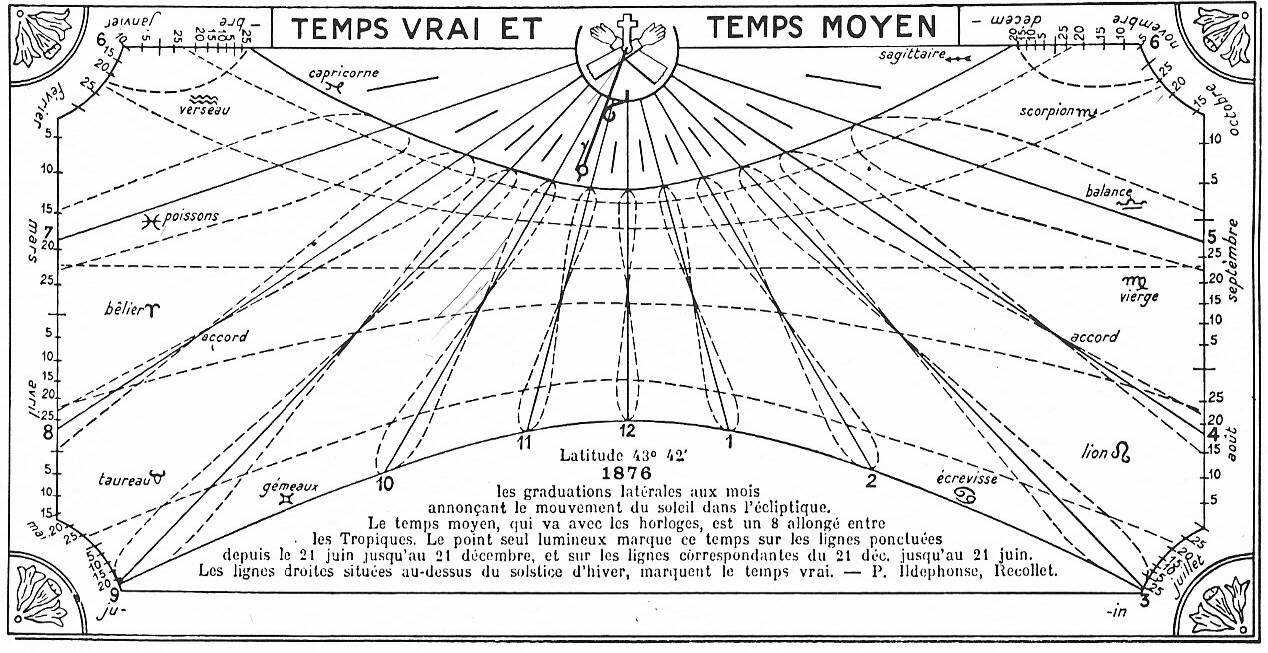

Of course, you can’t have Daylight Savings Time without Standard Time, which itself only came about after considerable wrangling and arm-twisting. Before the railroads really took off, there wasn’t really this idea of people all observing one exact time- they pretty much just went by whatever the local sundial said. It was only in the late 19th century that there began to be a need to have everyone on the exact same time. When the measure was imposed on Detroit in 1900, the city resisted, leading to a bizarre situation where half the town was following Standard Time and half was following the ol’ town sun dial for a spell.

The entire notion of Standard Time and Daylight Savings Time, of time zones and of setting the clocks ahead and back to suit human activities and preserve energy– it’s really one of the more brazen acts of Enlightenment thinking (along with, say, carving up the Middle East into distinct nation states– that one didn’t work out so well). One can only imagine the thrill and nervousness experienced by the person tasked with drawing a line down the map and declaring that the two sides would obey practices regarding something as basic as man’s relationship to the sun.

(Photo: stolen from my friend Jess’ Facebook page, of our friends hanging out in Dolores Park in the summer twilight).

(See this excellent site for more info on history and practice of Daylight Savings Time)

As my friend who accompanied me pointed out, “Both the band and everybody in the audience want to pretend it’s 1989.” It was very redemptive to see them deliver a completely amazing performance of all of their old hits, and get the adoring crowd response they deserved, as they were relegated to opening for the Throwing Muses or U2 back when the material was new, despite the fact that it would be largely responsible for chart-toppers like “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and many more. It was weird, though, to realize that it isn’t just the baby boomers who are aging rock fans anymore – there is now a whole new generation of aging indie scenesters to pay the $60 cover charge to a show like this to transport them back to the halcyon days of 1989.

As my friend who accompanied me pointed out, “Both the band and everybody in the audience want to pretend it’s 1989.” It was very redemptive to see them deliver a completely amazing performance of all of their old hits, and get the adoring crowd response they deserved, as they were relegated to opening for the Throwing Muses or U2 back when the material was new, despite the fact that it would be largely responsible for chart-toppers like “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and many more. It was weird, though, to realize that it isn’t just the baby boomers who are aging rock fans anymore – there is now a whole new generation of aging indie scenesters to pay the $60 cover charge to a show like this to transport them back to the halcyon days of 1989. Although the film did eventually succumb to the criticism that I, and doubtless many others, thought of even before we saw it – “Is this 20-sentence book really going to lead to a satisfying feature-length film?” – it was nevertheless very powerful at times, especially in the opening scenes where we see how isolated Max is in his childhood world, and also, to a somewhat lesser extent, when we see how the petty jealousies and resentments from which he is fleeing exist even in his new wild kingdom, leading him to sail away back home to his still-warm supper.

Although the film did eventually succumb to the criticism that I, and doubtless many others, thought of even before we saw it – “Is this 20-sentence book really going to lead to a satisfying feature-length film?” – it was nevertheless very powerful at times, especially in the opening scenes where we see how isolated Max is in his childhood world, and also, to a somewhat lesser extent, when we see how the petty jealousies and resentments from which he is fleeing exist even in his new wild kingdom, leading him to sail away back home to his still-warm supper.

I loved Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds — I think it was the first movie I’ve seen since Pulp Fiction where I immediately wanted to go see it again. Not surprisingly, it is proving somewhat controversial — one friend reported that he and his mother walked out when they “realized that we were in for two-something hours of Hogan’s Heroes II,” and a number of people have noted that there is something a little uncomfortable about watching a blatantly cartoonish and unrealistic story of rampaging American soldiers capturing, torturing and murdering prisoners of war, even if they’re Nazis. During Hitler’s big scene, I couldn’t help but think of all the frivolous Youtube homages that we’d soon be seeing based on it.

I loved Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds — I think it was the first movie I’ve seen since Pulp Fiction where I immediately wanted to go see it again. Not surprisingly, it is proving somewhat controversial — one friend reported that he and his mother walked out when they “realized that we were in for two-something hours of Hogan’s Heroes II,” and a number of people have noted that there is something a little uncomfortable about watching a blatantly cartoonish and unrealistic story of rampaging American soldiers capturing, torturing and murdering prisoners of war, even if they’re Nazis. During Hitler’s big scene, I couldn’t help but think of all the frivolous Youtube homages that we’d soon be seeing based on it.

Yesterday, I made my annual attempt to develop an interest in Radiohead. As usual, it lasted about 20 minutes. We’ll see what happens in 2010, but 20 minutes seems to be the standard. I have 7 Radiohead albums that people have given me and yet have probably played only about 10 songs on those albums. (Clarification: I’ve heard Radiohead songs zillions of times when someone else put them on or they’ve come on the radio, so it’s not like I haven’t been exposed to them; I’m just talking about how seldom I’ve personally chosen to listen to them). About once a year, I choose an album, put it on, and experience an immediate swell of respect and regard for the band, followed by an almost immediate lapse into disinterest. After a few songs, I realize I haven’t paid attention for the last 10-15 minutes and terminate the exercise.

Yesterday, I made my annual attempt to develop an interest in Radiohead. As usual, it lasted about 20 minutes. We’ll see what happens in 2010, but 20 minutes seems to be the standard. I have 7 Radiohead albums that people have given me and yet have probably played only about 10 songs on those albums. (Clarification: I’ve heard Radiohead songs zillions of times when someone else put them on or they’ve come on the radio, so it’s not like I haven’t been exposed to them; I’m just talking about how seldom I’ve personally chosen to listen to them). About once a year, I choose an album, put it on, and experience an immediate swell of respect and regard for the band, followed by an almost immediate lapse into disinterest. After a few songs, I realize I haven’t paid attention for the last 10-15 minutes and terminate the exercise.