A few weeks ago, former guest-blogger Grandjoe wrote me with the following evocative request:

I wonder if you could help me identify a print that I saw in Sarah’s classroom, on “Grandparents and Special Friends day.” Though not knowing either the artist or the title of the picture, I don’t see how it could be tracked down.

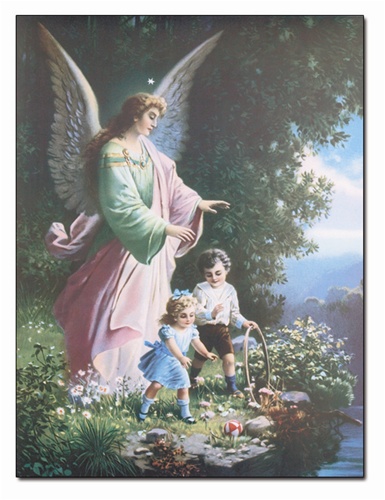

At first glance, I didn’t pay much attention to it. A somewhat kitschy idealization of childhood, late 19th century, probably English or American. A brother and sister gamboling in a meadow, being watched over by a guardian angel who is behind them. (She’s ethereal without having wings.) But on second glance, a sinister subtext suggests itself. The meadow is on the verge of a cliff . A lovely flower grows at the edge if the cliff, the blossom drooping over into space. The direction of the boy’s gambol is such that he might easily be attracted by this enticing flower. Similarly, the girl might catch sight of a white butterfly that is fluttering towards the brink. The viewer’s apprehension would be allayed by the presence of the angel, if she were not gazing off to the side, not directly at them, apparently lost in a a vision of celestial bliss. It’s not at all clear that she would get to them in time.

For me, the picture documents the dread that must have constantly assailed parents at a time when medicine was helpless to save children from premature death. No doubt parents are still anxious, but nowadays the threat is not so dreadful that it has to be hidden, as in this picture, behind kitschy denials of reality.

It turns out that this tableaux describes not one but probably hundreds of prints from the Victorian era. It seems that ‘child in close proximity to cliff while Guardian Angel observes from a short distance behind’ had a similar cultural currency in those days as Lamborghini or Che Guevara posters did in my childhood. Witness variations on a theme:

You get the idea. What’s interesting (sort of) is the sameness of pose and dramatic framing from image to image. If you imagine an urgency scale of 1 to 10 where 1 equals no problem, you’re just hanging out in a field… plus you’ve got a guardian angel behind you and 10 equals you’re toast. you’ve fallen over the edge and not even your guardian angel can save you, these images all seem to clock in at about 7 or 8. As evidence, note the general serenity of Angel’s expression but the similar outstretched reach in almost every instance.

But the best find from all of this turned out to be a fairly unrelated set of illustrated proverbs I found from the same period. It’s interesting to view mass media from a time before the all-consuming hobgoblin of irony entered the picture. Back then, you could simply place a moralistic statement under a drawing illustrating the same principle and call it a day. Nowadays, promising writers drive themselves up the wall trying to deal with the problem of what we really mean and what we don’t.

Here’s a sampling of these proverb woodcuts I came across, presented with a ranking from 1-10 regarding their relevance to modern life:

8.0. Relevant. My friend even used this phrase not too long ago when I asked him if I could crash on his sofa.

5.o. Gets points for the fact that this phrase maintains tenuous cultural currency. But nothing here seems to be trending towards a good end. I feel like I’m lacking some context.

3.5. Good point… but the unintentionally humorous illustration makes this feel like something out of the Gashlycrumb Tinies.

9.5. Timeless wisdom. Applies to both Prince William and Barack Obama.

1.5. Sounds persuasive, but what’s a shoal?

7.5. Same take-way as Bob Marley’s ‘Small Axe’. Thumbs up for continuity!

1.0. As a secularist, I say extremity sucks. At least I can spell it correctly.

3.0 Who’s preventing whom from what cure now?

6.0 I’m not sure I get the point, but that’s some damn good donnybrooking there.

(Top image: kickass William Blake illustration. Not Victorian… and nothing to do with anything else in the post… but when would I ever get a pretext to post this again?)

Awesome prints. I too am not sure how to interpret the shoal one (although I do know what a shoal is). The idea must be that the person suffering adversity has a better understanding of that adversity than any outsider? (Like, you can’t know the shoal until you’re stuck on it yourself.) “Climb not too high” = anti-class ambition, I suppose.